Do your neighbours have a noisy love life? Consider yourself lucky that you are not a fruit fly! Anne von Philipsborn’s group has discovered that female fruit flies sing by pulsed wing vibrations while they are copulating.

The new study, published yesterday in Nature Communications, was led by experts in behavioural genetics and circuit neuroscience in Drosophila at DANDRITE. The researchers’ findings on Drosophila sexual behaviour are important for understanding the complexity of neurocircuitry and behavioural genetics. In this article, first author of the paper PhD-student at DANDRITE Peter Kerwin and Group Leader Anne von Philipsborn explain their new findings.

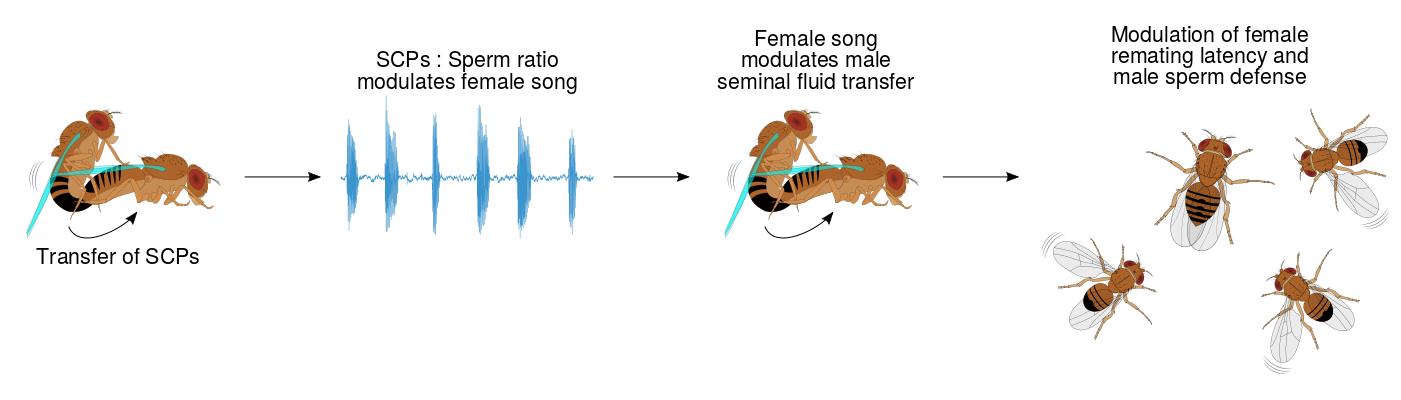

The Philipsborn lab have investigated the acoustic behaviour and the underlying neuronal and sensory mechanisms in fruit fly reproduction and discovered that female fruit flies sing while they are copulating. By vibrating their wings quickly, they produce a high-pitched chitter while the males ride on them for the 15-30 minutes they are coupled for mating. The females use a special, female-specific set of nerve cells for this behaviour.

Fruit flies, a widely used model organism for Genetics, Biomedicine and Neuroscience research have been known for their love songs before. Since the 1960’s, it is known that male flies sing to court females and convince them to mate - a musical talent which was thought to be unique for males. Why would fruit fly females sing when they have sex? Basic representations of pleasure and aversion can be found in insect brains, but from a scientific point of view, barely anything happens just “out of pleasure”. Instead, behaviours have evolved because they gave animals performing them some advantage in surviving and reproducing.

The Philipsborn group still do not know exactly the function of female copulation song, but an answer might come from seminal fluid. Males not only transfer sperm, but also seminal fluid, a biochemically fascinating soup with many active and mysterious ingredients, which influence for example fertilization, immune response and storage of sperm. In the case of fruit flies, males with compromised seminal fluid fail in making their mates sing. At the same time, these new findings suggest that the female song can influence male seminal fluid transfer, changing how receptive the female is to her next suitor. So even for flies, love is complicated, and their pillow talk has still some secrets to discover for indiscreet scientists.

In the future, the Philipsborn group wants to better understand how ejaculate is sensed by the female, how the male nervous system controls seminal fluid transfer and how differences in male and female brain give rise to the two different types of love songs.

The publication can be read in full at the Nature Communications Website

Click here to learn more about the Philipsborn lab and their research within molecular cell biology, brain circuitries and behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster.

Credit: Anne von Philipsborn and Peter Kerwin.